On Sunday May 14, Wim Andriessen died. He was 78 years old. He was a strong player, but the Dutch and later also the international chess world is mainly indebted to him for his activities as a chess journalist, editor and publisher.

In Dutch chess circles, it was a long-time standard joke that to assure financial ruin, a man should spend his money either on loose women or on the launch of a chess magazine. Wim did the latter in 1968 when he founded the magazine Schaakbulletin (Chess Bulletin) and eventually he would prosper, not spectacularly in the financial sense, but in the modest way that he had envisioned at the start: to set up a quality chess publishing company and make a decent living from it.

A few years later, in 1971, Wim made the daring step to give up his job as a cartographer at the Wageningen Agricultural University. He not only left his job, but also his wife, his children and his house in the provincial city Wageningen. Like the three sisters in Anton Chekhov’s play who were yearning to move to Moscow from their provincial backyard, Wim was yearning for Amsterdam, with the difference that he indeed went there to fulfill his dreams. For a long time he used to complain about the arrogance of the chessplaying natives of Amsterdam, but I think he enjoyed himself.

Schaakbulletin had a humble beginning in 1968. Alexander Münninghoff, who in 1985 edited an anthology of articles from the magazine under the title Hartverscheurende schimpscheuten (Heart-rending Gibes), described the first issue as an amiable rag, put together by some boys from Wageningen who didn’t have a clue what they were doing and with a cover of recycled toilet paper on which Wim Andriessen, with undisguised nepotism, had allowed a member of his family to play havoc with a chessboard.

The board was wrinkled and set up wrong, with a black h1-square. Münninghoff pretended to interpret the wrong-colored square as a sign that the magazine wanted to be controversial from the start. Perhaps, or perhaps the artist had no idea what he was doing.

I didn’t know it at the time, but apparently the name Schaakbulletin was inspired by the Dutch Vietnam Bulletin, which opposed the American war in Vietnam. Wim was a man of the left and he even played for a while with the disastrous idea of turning his magazine into a cooperative controlled by the subscribers. In fact, he wasn’t a man for shared leadership.

In an early issue, there was a photo of Wim and two helpers with heaps of papers, outside in front of a public garbage bin. The caption was something like: “The editors handling incoming mail.”

It was a merry and wanton magazine, but it was also more than that. In Schaakbulletin, Hein Donner published magnificent anathemas, Jan Timman reported on the struggles on his way to the top and Tim Krabbé laid the foundations of his monumental collection, Chess Curiosities.

Things went well. Wim founded a chess shop, where we came to play blitz, and he published not only the magazine, but also books. In 1984 he went global by replacing the Dutch Schaakbulletin by New in Chess, which is written in English or, as detractors have said, English-as-a-second-language.

Anyway, it is the magazine to which world champions and most of the top players have contributed articles. I am a regular contributor too, and I do not hesitate to say that for us from New in Chess, New in Chess is the finest chess magazine in the world.

Around the beginning of this century, Wim sold his company, though for quite some time he remained involved as an advisor. He was living in Alkmaar by that time, and for his local club De Waagtoren he was a trainer of young talents and editor of the website. Last year he was made a honorary member of that club.

I had a look at the club’s website and was reassured to find that he had still been capable of a polemic thrust, just as he had so much liked to do in the past.

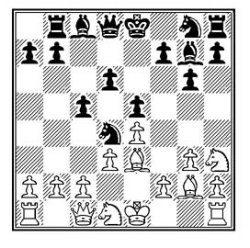

From the game in the viewer, I would like to point out one particular moment.

Constant Orbaan-Wim Andriessen, Turmac tournament Zevenaar 1967, after Black’s 9th move.

Who would play 10.Ng1 in this position? Only Constant Orbaan. At the time he was the chess contributor of the newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad and much later we would both work for its successor, NRC Handelsblad.

Constant liked his knights so much that in the initial position he used to place them with their faces turned towards himself. I have never seen anybody else doing that.

Early knight retreats appealed to him. When at the Dutch championship of 1950, after 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Bxc6 dxc6 5.Nc3 f6 6.d3 Bd6, Orbaan played 7.Ng1, his opponent Hein Donner stood up and shouted through the tournament hall for all to hear: “This man is mad!” Orbaan won that game, but it must be said that his knight retreat in that case had a clearer strategic motivation than that in the present game against Wim Andriessen.

Here is the complete game, with Hans' notes.